Breast Implant Developments

Silicone breast implants have changed in incremental steps over the last 50 years. Some changes have been good, others less so, and research and developments continue to be made by manufactures. The first silicone-filler breast implants were introduced to the market in the 1960s. These are now termed ‘generation one’. They had a thick outer layer (the shell) and inside was a thick silicone gel. They were superseded in the 1970s by ‘generation two’ implants, which contrasted greatly, having been made with a very thin shell, and they were filled with a very thin, almost watery, silicone gel. In the 1980s the design modification was to add a barrier layer to the outer shell. This was a thin layer sandwiched within the outer shell to reduce silicone bleed that might otherwise occur through the outer layer. Silicone bleed is a subtle seepage of some gel that may occur through an implant shell that has not ruptured. When it occurs it normally only allows a small amount of silicone to escape, but this is clearly something to avoid. This is analogous to a balloon that deflates a little as air molecules escape through the latex of the balloon. The barrier layer greatly reduced this problem and the gel in the implant was also made more viscous, with refinements and improved consistency in the molecular chain size of the silicone molecules. In the 1990’s the 4th and 5th generation silicone implants were developed with even thicker ‘more cohesive’ gels, with the firmest type called a ‘form stable’ implant. This enabled the anatomical teardrop implant to be produced that would maintain shape. The shell of the implants was also slightly thicker than the previous 3rd generation type.

Breast Implant Textures

The outer layer of a silicone implant can be smooth, micro polyurethane coated (sometimes referred to simply as ‘MPU’) or textured. The outer layer is in direct contact with the under surface of your breast, and so the surface of the implant can also influence the feel of the implant, and in the longer term it can influence the success rate or occurrence of complications. In broad terms we now recognise that the textured surface implants vary more widely according to the manufacturer of the implant. They vary by the degree of roughness of the textured surface and the way your body responds to the implant’s presence. When the surface of the textured implant has a high roughness, it can be beneficial in reducing implant movement, such as reducing the rotation risk of a teardrop shaped breast implant. It does this by enabling the surrounding tissue to attach to the rough surface. This rough surface, and tissue attachment has also been debated to reduce potential capsular contraction of the implant. And capsular contraction has been one of the commonest unwanted problems with implants affecting around 10-20% of patients within 10 years. It was also recognised that the textured implants had less association with capsular contraction than smooth shell implants if they were sub glandular, although texturing seemed to confer no benefit when sub-pectoral positioning was chosen. But in recent years, research has begun to suggest that texture might not be as good as previously thought. This is because the texture itself creates a far higher ‘surface area’ to the implant’s exterior which allows bacteria a better chance to attach to and hide in the minuscule nooks and crannies of the roughened surface, presumably getting in there at the time of implant placement. Yes, despite the implants being inserted in the clean environment of an operating theatre, many factors can lead to unintentional microscopic contamination of your implant. Such minor contamination does not result in infection but the bacteria can then co-exist on the implant surface in what is termed a ‘micro biome’. Bacteria might also get to your implant through the blood stream (e.g. when having a root canal procedure at the dentist) or through the breast (mastitis from a cracked nipple from breast feeding). Some evidence suggests that certain bacteria in a micro biome trigger capsular contraction. This state of affairs can exist for years with little or no change, or it can cause gradual hardening of the implant. As it becomes distorted it will affect the shape of the breast and sometimes also cause discomfort – this is grade 3 to 4 capsular contraction. In very small numbers of patients this chronic stimulation of your immune system might even be the cause of a rare lymphoma that is associated with breast implants. So choosing the implant texture can play an important part in both the cosmetic outcome but also the long-term safety.

Macro Textured, Micro Textured or Nano Textured?

Some implants have texturing that is more rough or less rough than others, and you might hear the terms macro-textured, micro-textured, and nano-textured. There are no good comparative studies to assess these, and some of the newest textures are associated with new implant manufactures where there are insufficient numbers of patients with the implants, or length of follow up to make big claims that one is superior to another. Some of the texturisation techniques are also different with imprinting, the use of salt crystals, or chemicals being used.

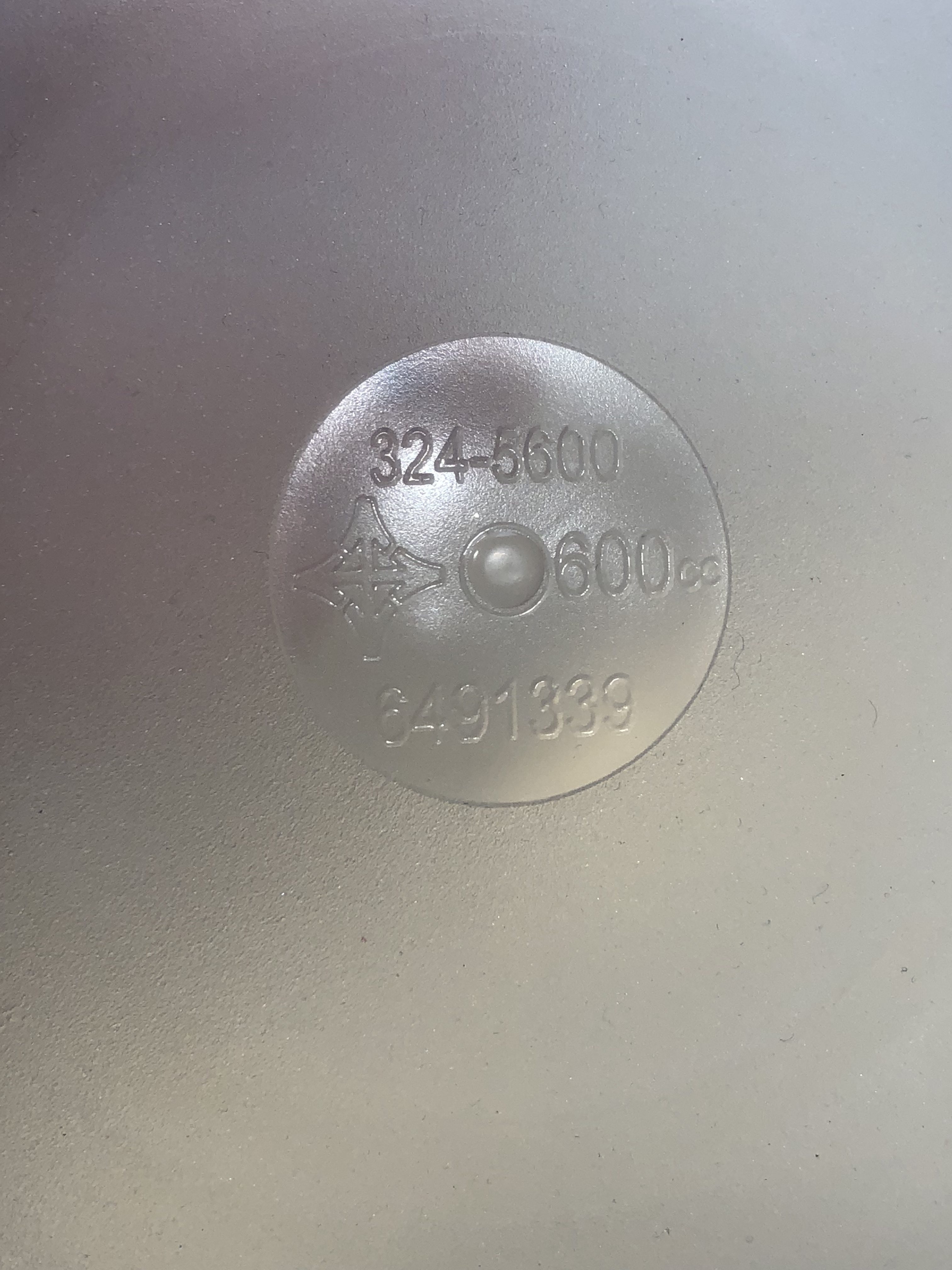

Micro-textured breast implant

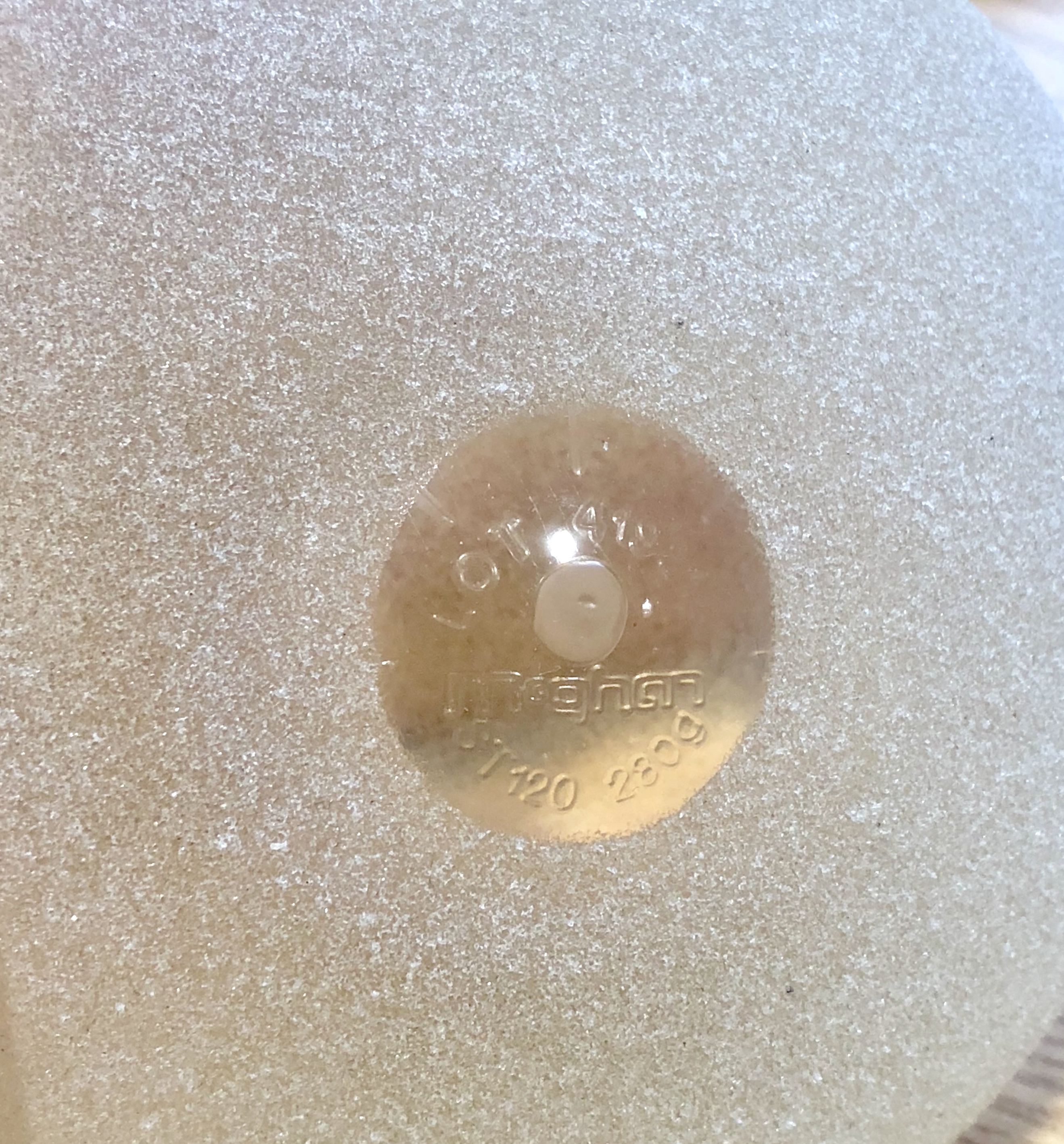

Macro textured breast implant – Manufacturer McGhan

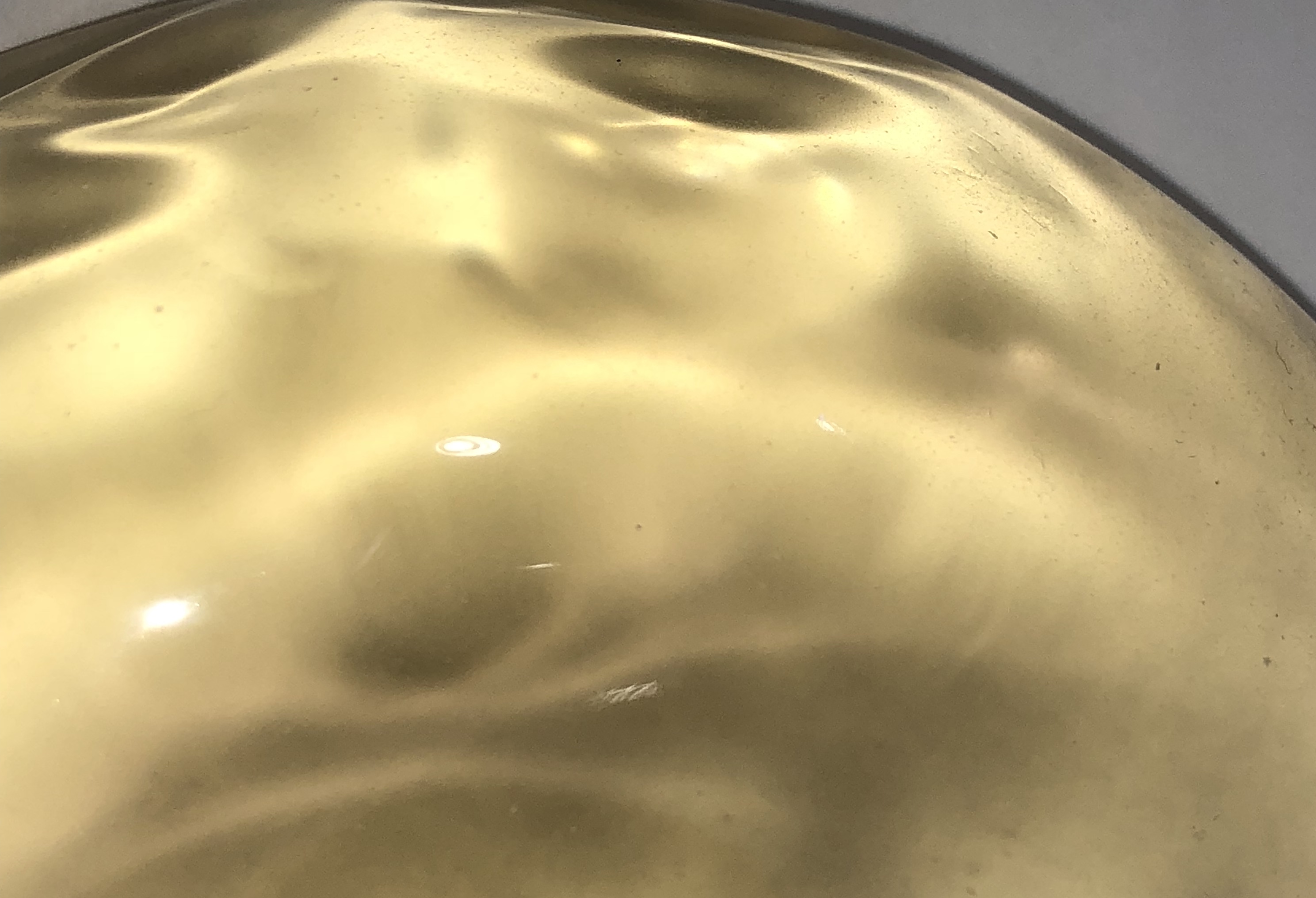

Smooth surface breast implant

We do know that the lesser textured types do not allow tissue integration (adherence) and this might affect choice if using a tear drop implant. The friction from the slightly textured surface of a micro-textured implant is thought to reduce the risk of implant rotation despite there being no tissue integration. Whether the nano-textured implants behave any differently to a smooth surfaced implant is currently unknown though. We have to be careful of potential manufacturer’s claims relating to their textured surface that are not supported by robust research or adequate years of follow-up.

Which Texture of Breast Implant Should You Have?

It is always better to consider your implant choices, by aiming to reduce risks in a balanced way. You need to take account of the pros and cons of the different implants and their surfaces. Your surgeon should guide you here; but do be cautious in case they are tied to one manufacturer’s product. Sometimes there is a reason to choose some texture to the implant surface, but other times going for a smooth surface might be preferable. For example, if an anatomical implant (this has a tear drop shape) is the best choice for you, you need some texture to stop it from rotating. In years gone by we might have used the anatomical implant with the most texturing, maximising the adherence possibilities of your tissue onto the textured implant surface, to reduce rotation risk. But these days I would avoid that type of implant if possible and so where an anatomical implant is chosen or indicated, I would advise someone to use a low textured implant (I refer to this as a micro textured implant). The reason for this relates to the our increasing understanding that there is a small but specific lymphoma risk that exists with breast implants. This low lymphoma risk is predominantly associated with textured implants, and the most textured implant types are over represented amongst reported cases. In addition, if you are opting for a sub-muscular implant, and you are suitable to have a round implant (as opposed to the tear drop shape) then it is sensible to consider a smooth surface implant, and avoid any texturing. This is because there have so far been no clinical reports in any country of the rare implant-associated lymphoma in patients who have only ever had a smooth implant. There is perhaps more difficulty if you are considering sub glandular implants as smooth implants are associated with a greater capsular contraction rate in this position than their textured counter parts. So if avoiding sub-muscular placement is a priority, then in this situation it is not unreasonable to choose the micro-textured implants, where the risk of capsular contraction is lower than with a smooth, and the risk of lymphoma is regarded as being sufficiently rare. Although it is not zero, it is thought to be a risk of only around 1 in 20,000 to 1 in 86,000 depending on where you source the data.

What Else Can You Do To Lower The Risk Of An Infected Implant?

Overt infection leading to loss of your implant within the first 6-weeks of your breast enlargement is uncommon, but it does occur. Micro biome formation is probably much more common. To reduce your risk, you almost certainly need to pick your surgeon and the hospital where you have the surgery done very carefully. The techniques used to lower the risk of inadvertent contamination require a committed surgeon who is motivated to lower a risk that is hard to measure, but is clearly important. This requires someone who is a technically excellent specialist surgeon in that field (ie breast surgery), with years of consultant level experience, and who audits his results. You may also want to select the hospital based on the Care Quality Commission reports. In addition you should ask your surgeon what their infection rate is and what technique they use to lower risks. They should be able to rattle off at least 14-points.

In my practice with over 14 years as a consultant breast surgeon performing cosmetic breast augmentation as a specialist, I have not had a single infected implant in any patient undergoing primary breast enlargement. I use well defined techniques and I am obsessive with the way I work to get these results. But I am never complacent and I continue to strive to learn, to understand the emerging science, and to provide the optimum results for my patients.